15 March 2024

Our finest living artist schooled in goodness of the human spirit

8 minutes

How Frank Auerbach was saved in wartime by education pioneer Anna Essinger

Frank Auerbach is, arguably, our finest living artist. He’s an old and modern master who over many decades has focused on a very few people and places.

Auerbach’s new exhibition ‘The Charcoal Heads’ at The Courtauld Gallery, in London, is much admired by critics – his models are breathing and feeling because it’s the art of life, set against his own, which changed forever when his parents sent him from Berlin to England to escape the Nazis in 1939.

Auerbach was given safe haven in a remote boarding school on the North Downs in Kent by head teacher Anna Essinger, who secured refuge to more than 900 children between 1933 and 1946.

Essinger’s move to England

|

(Image: Anna Essinger) |

The story of Anna Essinger and her Herrlingen School’s move from southern Germany to England occupies a unique place in education history. Essinger subscribed to the Reformpadogogik, a form of learning with an emphasis on developing an inquiring mind. She was born in Germany and had been sent to the US to be educated during the First World War. She returned to her homeland full of educational ideals and in 1925 set up a boarding school to put her contemporary teaching methods into practice. In 1933, every school in Germany was ordered to fly the swastika flag on Hitler’s birthday. Essinger responded by arranging an all-day outing for pupils so the flag, raised by a caretaker, flew over an empty school. When the government decreed no Jewish children could sit the Arbitur, the high school leaving certificate, Essinger had the foresight to realise it was time to leave Germany. As a non-practising Jew with links to the Quakers, she contacted all of her pupils’ parents and called on her circle of influential friends to help find an alternative school in Europe. Bunce Court, a manor house hidden between Lenham and Faversham, in Kent, became the preferred option. In October 1933, Anna and her two sisters split the 65 pupils into three groups and to attract the least attention each left from a different city to arrive in Ostend and took the ferry to Dover for a new life in England. Tante Anna (Aunt Anna), as she was known to her pupils, taught them to be self-sufficient in a foreign country, realising many would never return home or see their parents again. Although great emphasis was put on the pupils to pass the Matriculation exam, practical lessons were equally important. The children learned how to repair clothes, grow vegetables and prepare food in the kitchen. |

Staff, who were often refugees or, later, British conscientious objectors, shared chores with the pupils and everyone called each other by first names. Religion did not play much of a role but at mealtimes everyone would link hands to say ‘Children love each other and if that doesn’t work, at least tolerate each other’.

There was plenty of time to play in the bluebell woods and fields or make pocket money by picking cherries while everyone was encouraged to appreciate the arts and music. Plays and concerts were held in the school’s amphitheatre and the local community, friends and supporters were invited to watch performances from Shakespeare to The Magic Flute.

|

The school’s rural idyll was crudely disrupted by events in Germany. In 1938, the full horror of Nazism began to unfold and groups of bewildered children from the Kindertransport programme arrived at Bunce Court. These displaced youngsters brought with them the realities of persecution and prejudice. The school expanded to three temporary premises to accommodate the overflow. Frank Auerbach was seven when he arrived at Bunce Court from Berlin, in 1939. He never saw his parents Charlotte and Max again and the school became his home for the next decade. Auerbach, 93, who has a home and studio in London, said: “Bunce Court was my home. I consider myself fortunate to have been one of the children in that unique community. “I was scared of Anna Essinger, in a respectful way, but I may have been a fairly nervous child. “She was as strong a character as Margaret Thatcher, though with different ideals and in a different situation. It was at Bunce Court I realised elaborate possessions, treats and, to a large extent, status and money, were not essential to a rich life. I cannot imagine a better home.” Auerbach also remembers house-teacher and nurse Gwynne Angell, who at the time was only 18. He said: “She was very sympathetic and taught us perfect English.” Every night Gwynne would read the younger children bedtime stories. Gwynne, who lived to 103, and passed away in 2013, said: “I became a mother to the children. I loved them. Even when the boys and girls were in their late 80s I still had strong feelings for them. “Frank Auerbach was such a shy child. He started to draw pictures for me when he was about seven or eight. I kept them all, followed his work and went to see the exhibitions. He knew Lucien Freud – but I was not much taken with his work.” Auerbach said he was flattered that his former nurse had remembered him, saying “I was a rather quiet child so I am touched that she was aware of my work and had taken such an interest in my painting. I have fond memories of Gwynne and my respect for the way she dealt with the uprooted children she cared for has grown over the years.” |

(Image: Children at Bunce Court during wartime) |

Living in denial

In March 1943 Auerbach’s parents were transported to Auschwitz and their censored 25-word letters forwarded by the Red Cross stopped arriving. The news that they had been taken to a camp and killed was gently passed on to the 12-year-old Auerbach.

Auerbach says: “I did this thing which psychiatrists frown on; I was in total denial. It’s worked well for me. I went to a marvellous school. There’s just never been a point in my life when I wish I had parents.”

After finishing his education at Bunce Court Auerbach would return for the summer holidays, painting and ‘doing a bit of practical work’. He was accepted at St Martin’s School of Art in 1948 but instead opted for Borough Polytechnic to attend David Bomberg’s classes where he started using charcoal.

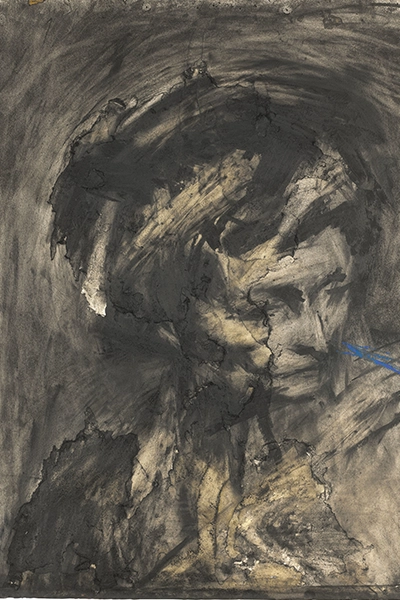

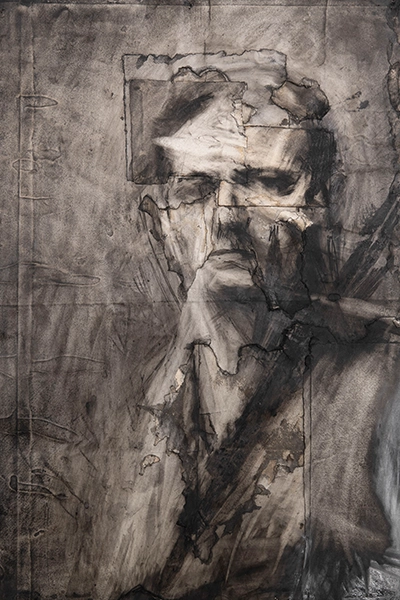

“These vigorous charcoal drawings, more vigorous than perhaps other students, began when Auerbach was just 17 or 18,” says Barnaby Wright, deputy head of The Courtauld. “Being able to rub out, manipulate and rub through charcoal suited him very well. The trauma in the work here at The Courtauld is quite intense, desperately trying to bring images to life, patching and repatching – this is when his trauma begins to show through.

“For Auerbach, a mark of a drawing is finished or nearly finished when it starts to surprise him, when it's still anchored to the person in front of him, to the experience of that person, but it has an element of surprise that doesn't any longer feel conventional. It feels like it’s broken behind, broken through, so it's a real thing.”

Visitors to The Charcoal Heads see drawings formed by blizzards of strokes and marathon effort, where often more is obliterated than rescued, heavily worked, capturing the impression of being brilliantly alive in the moment.

|

(Image: Frank Auerbach (b.1931), Head of Gerda Boehm, 1961, Charcoal and chalk on paper. Private Collection courtesy of Eykyn Maclean © the artist, courtesy of Frankie Rossi Art Projects, London) |

(Image: Frank Auerbach (b.1931), Head of EOW, 1959-60, charcoal and chalk on paper, Tate, London © the artist, courtesy of Frankie Rossi Art Projects, London) |

|

(Image: Frank Auerbach (b.1931), Self-Portrait, 1958, Charcoal and chalk on paper. Private Collection © the artist, courtesy of Frankie Rossi Art Projects, London) |

(Image: Frank Auerbach (b.1931), Head of Leon Kossoff, 1956-57, Charcoal and chalk on paper. Private Collection © the artist, courtesy of Frankie Rossi Art Projects, London) |

The Charcoal Heads runs to May 27, 2024. Bookings at courtauld.ac.uk

|

(Image: Frank Auerbach The Charcoal Heads at The Courtauld Gallery. Installation View. Photo Fergus Carmichael) |

Essinger’s place in history

The story of Anna Essinger and her school’s move from Germany to England occupies a unique place in education history. She had been born into a prosperous German Jewish family and after studying in the US became a lecturer at Madison University, where she worked during the First World War. She returned to Germany as part of a Quaker relief team.

Essinger believed that tranquil domesticity in rural surroundings was the most productive educational setting for children, alongside rigorous academic and social discipline, subscribing to the Reformpadogogik, a liberal educational path in which pupils were considered to be equal and community spirit was fostered. As the eldest of nine children, Essinger insisted her pupils should ‘love one another or, if this is not possible, at least respect one another’.

Bunce Court latterly accepted children who had grown up in concentration camps and others who had been active members of the resistance movement. Essinger steered many through their education certificate within two years rather than at the end of a whole school career.

As well as Auerbach, many other Bunce Court children went on to live extraordinary lives including musician and cartoonist Gerard Hoffnung, playwright Frank Marcus (The KillChelsea66xxing of Sister George), film-maker Peter Morley CBE and immunologist Leslie Brent. Artist Augustus John’s nieces Anna and Natalie were also pupils.

By 1948, there were moves to bring in new teaching staff but after the war had ended, the school had done its job and its life came to a natural end.

Essinger retired having justified her belief that children learned best through an understanding of ‘the essential goodness of the human spirit, a need to exercise tolerance and respect for all human conditions’.

|

(Image: The plaque at the former Bunce Court school in Kent) |

She stayed on at Bunce Court until her death in May 1960, aged 81. The property has now been split into several homes and a plaque engraved by Gerard Hoffnung’s daughter on the outside wall says “In memory of ‘Tante Anna’ Founder and headmistress at Bunce Court School, who gave a home and a sound education to hundreds of refugee children, mainly Jewish, during that time. Remembered with affection by so many for her great foresight, progressive educational endeavour, wisdom and compassion.” |

Auerbach at auction

Auerbach works at auction attract huge interest. At Christie’s 20th / 21st Century: London Evening Sale on March 7, 2024, The Studios under Snow, oil on canvas, painted in 1991, sold for £579,600 while Head of Jake – Auerbach’s son – an oil on canvas, painted in 2006, sold at £289,800. This beat the estimate of £180,000-£250,000 at Christie’s Post-War And Contemporary Art Day Sale on March 9.

Art insurance with Howden

Whether you have a large art collection or just a few pieces, you should check it has the correct insurance cover. You don’t always need a stand-alone policy to insure artwork, but it shouldn’t be insured as “Contents”. Our recommendation is that any art in any form is insured under the “Art and Antiques” section of your policy. Ensure there is a good description of each item, with size and images.

We also recommend that you get an up-to-date valuation. Make sure the valuation is for insurance purposes and that documentation is kept in a safe, secure, but memorable place in the event of a claim. We have a panel of recommended valuation companies that can assist by not only valuing your pieces now, but by also giving you up-to-date valuations going forward. Some of the insurers we work with will give a 25 per cent or even 50 per cent uplift for three years following a valuation to protect policyholders from rising prices.

To speak to Howden about your insuring your art call 020 8256 4901 or email art.insurance@howdeninsurance.co.uk